We will be looking at four major body parts. (These are not in a particular order.) Three are real, one is not.

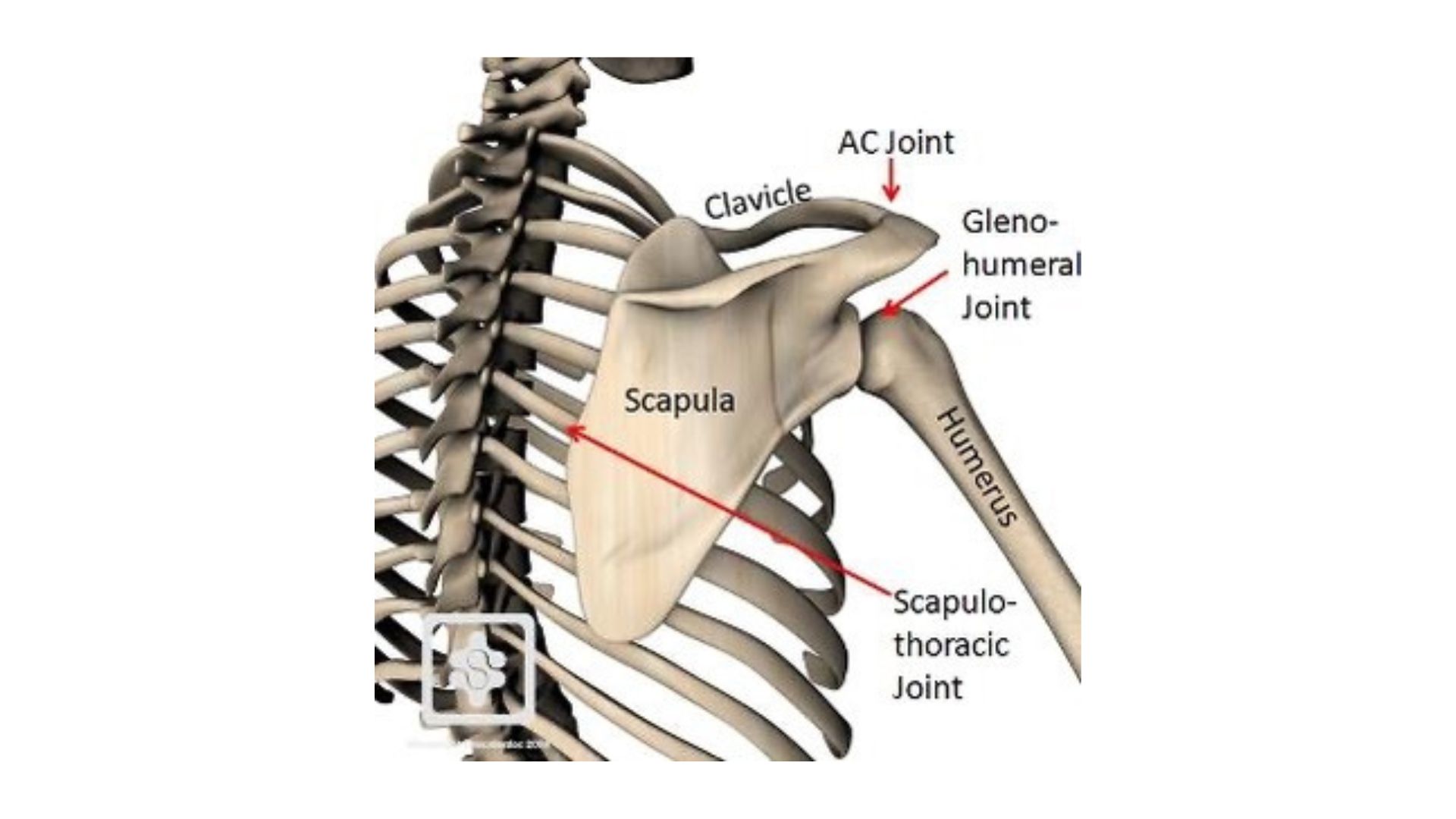

- Shoulder

- Clavicle

- Scapula

- Shoulder joint

The Oxford English dictionary definition of the shoulder is false. Despite its universal acceptance the shoulder has no actual function in our skeletal structure. It does not exist. There is no bony basis for the shoulder despite the claims of the profession of shoulder surgery. The shoulder joint is a valid anatomical structure and it also has a proper anatomical name, the gleno-humeral joint. Although the shoulder joint is treated as part of the shoulder it is in simple anatomical truth really only a part of the scapula. The shoulder region, despite its importance in medical literature, has no anatomical name and can never have one. There is no shoulder bone. It is simply an impressive shape, topology, or surface anatomy only.

Modern medicine has committed this major error because of its symptomatic, top down, and reductionist bias. This is associated with the professionalization of shoulder surgery in the 20th century but is also a historical bias. There is a clear historical debate over the role of the scapula going as far back as James Winslow’s 1733 An Anatomical Exposition Of The Structure Of The Human Body. Winslow pointedly declares: “the scapula is the principle, or rather only, Piece of which the Shoulder is formed” (vol. 1, sect. 3, p. 132).

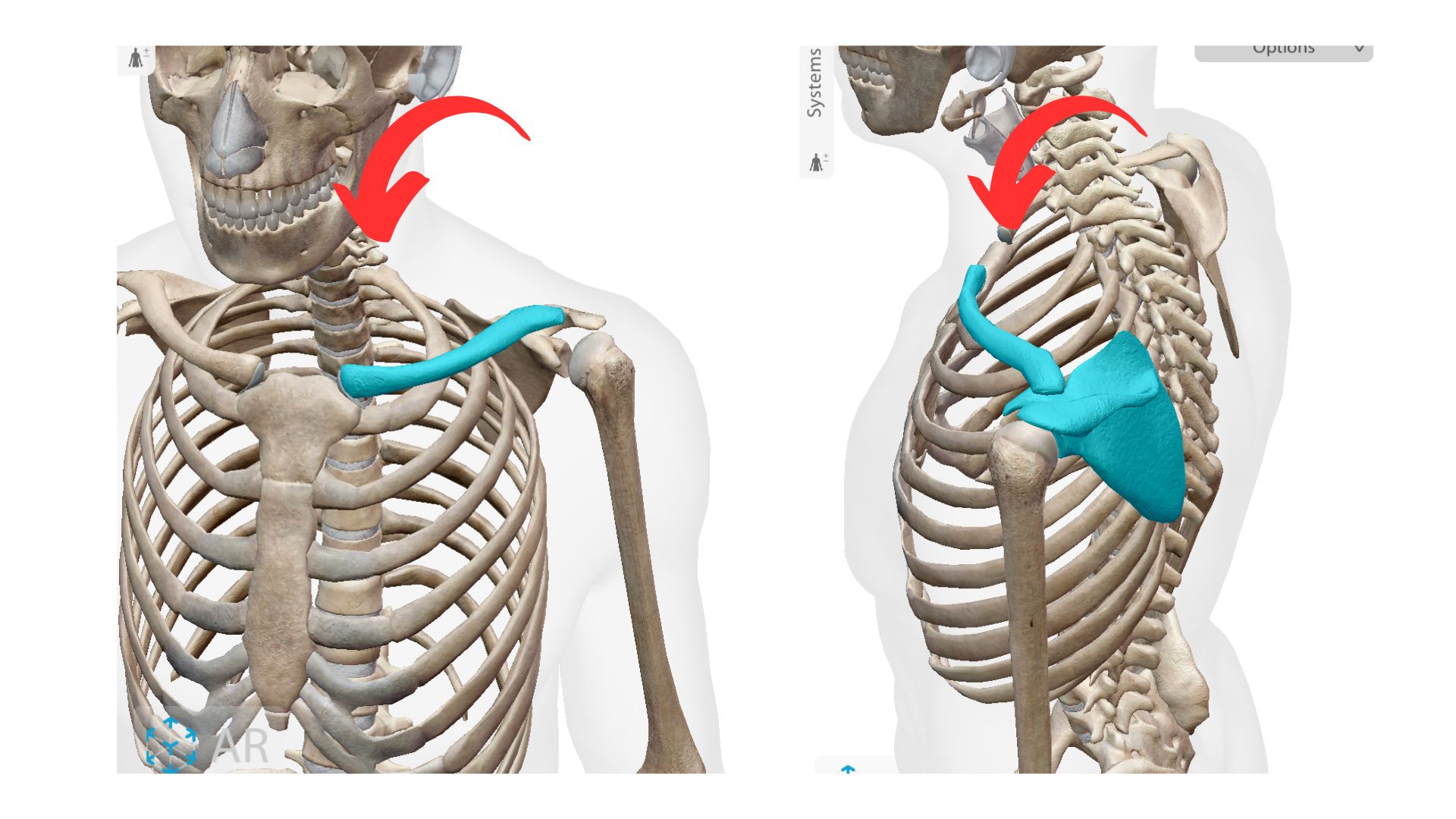

The scapula is what is called gross anatomy because it is readily visible and easily palpable. It is not difficult to see, feel, or move. The scapula is obviously the basis of the upper extremity and is its center of coordination. While scholars like Ben Kibler are now moving aggressively to affirm this point, the overwhelming bias against it still remains.

The Terminologica Anatomica has gone through several major revisions since 1895. Anatomical names are intended to be specific and self-evident (Sakai 2007). Anatomical specificity is very important for medicine and surgery. The absence of a formal anatomical name for something as major as the shoulder is a serious problem. Greek and Latin terms are used in a systematic way to indicate size, shape, function, relationship, quantity, and etc.

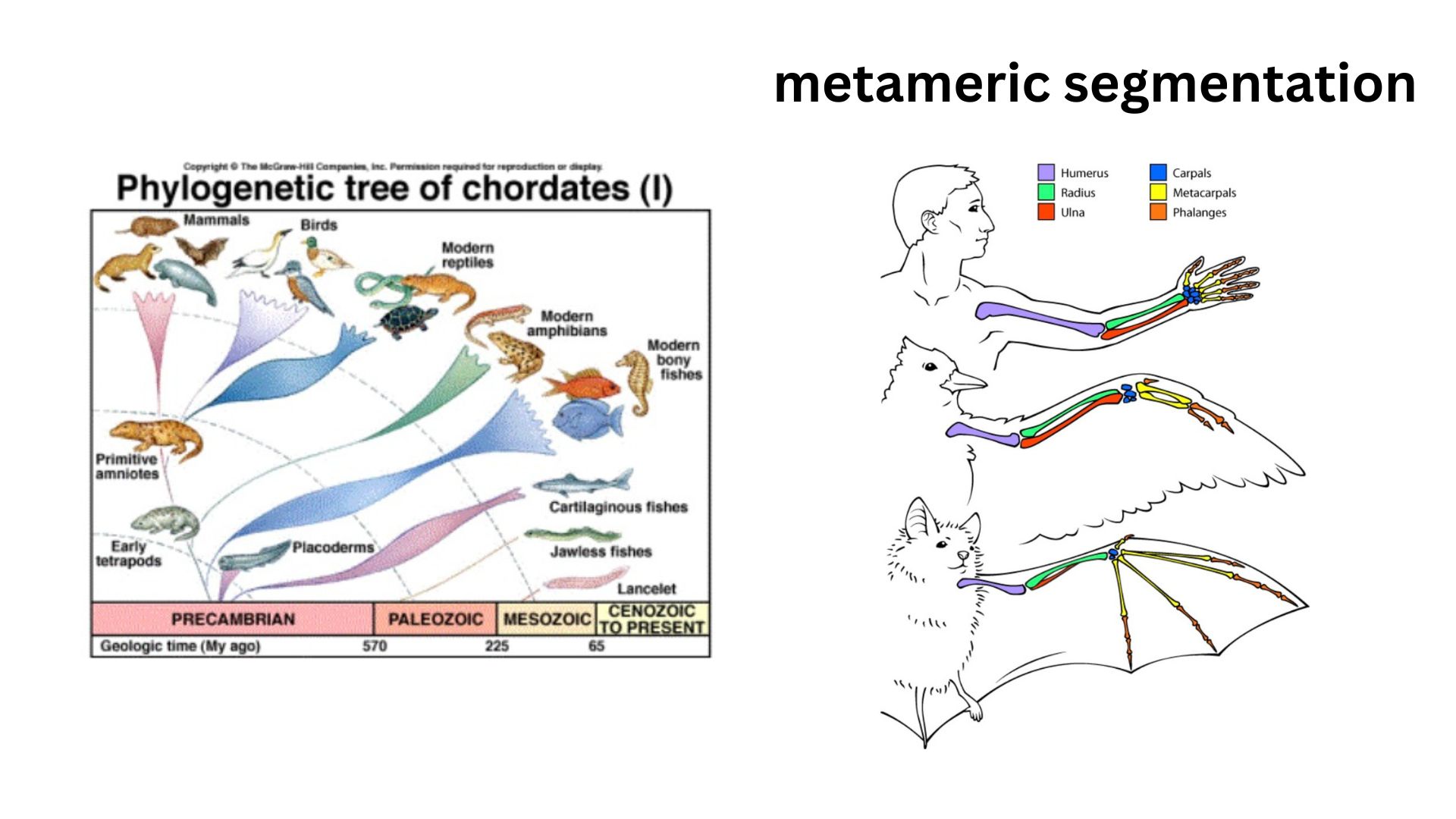

Throughout the chordate phylum, which includes all vertebrates, bodies tend to be organized according to a principle of metameric segmentation, in which structures like limbs and vertebrae are arranged in a linear series of repeating elements. Ordinal priority is a very important principle in anatomical naming and kinesiology, reflecting the fact that structures closer to the core tend to have causal priority. This affects the way we understand the attachments of muscles and their actions, with specific roles assigned for origin, insertion, and action based upon relative proximity to the core. Larger muscles and bones are more central and so more causal within the structure.

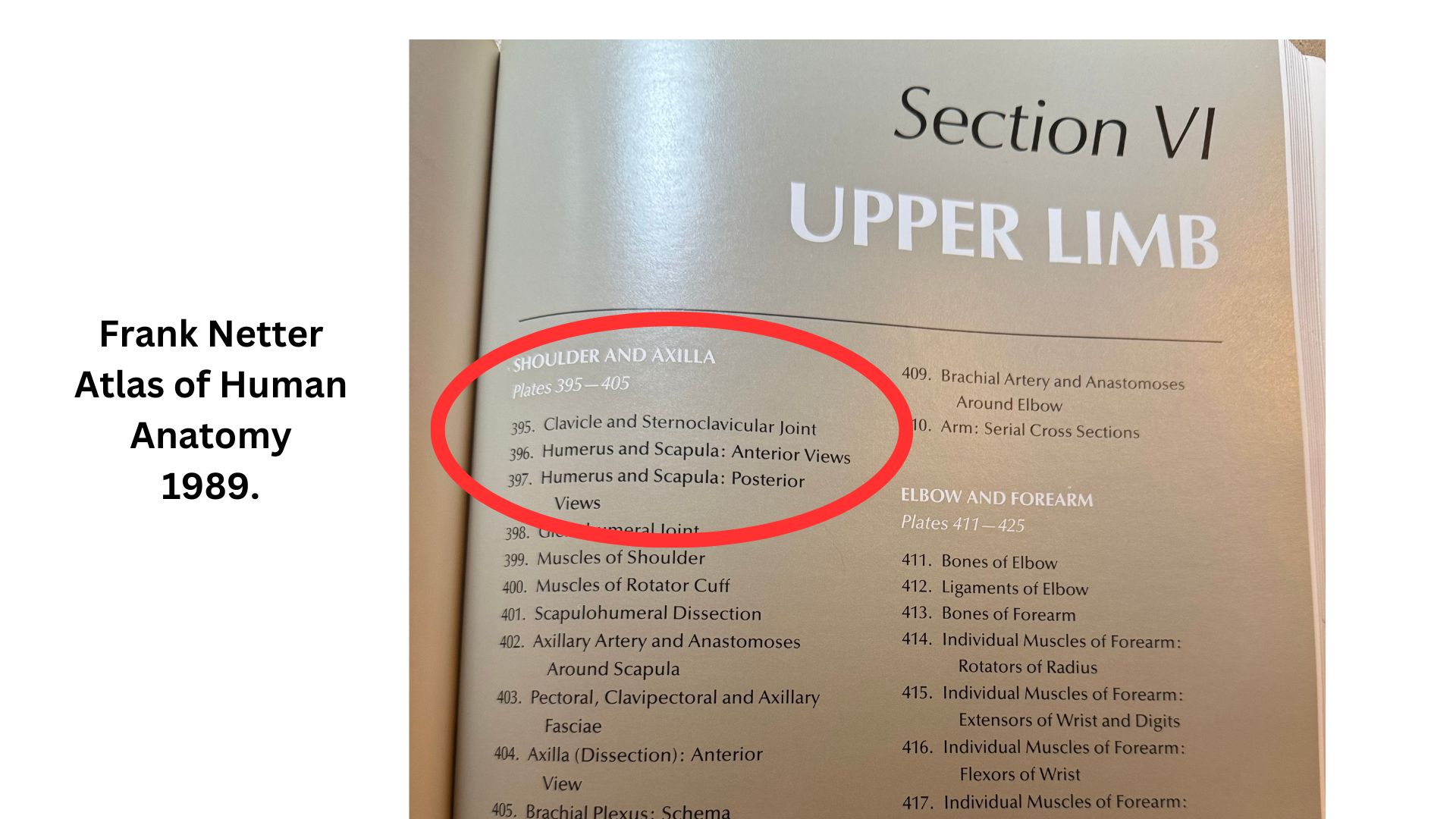

Ordinal priority in the names of muscles and bones reflects their relative importance in the system. For example larger and more proximal bones are also listed and discussed first as a rule in anatomical texts. Their ordinal priority determines whether they take the subject or object position in statements and whether they are seen as active or passive, important or less important. In almost all anatomical texts The clavicle is listed above the scapula. This is an error that we will discuss this more in detail below.

The conventional anatomy of the human shoulder violates all of these principles. There is no sentence about the kinesiological movement of our skeleton where the shoulder can properly be the subject or object of an action verb. We can carry a bag on our shoulder but this is not a formal kinesiological statement; it a functional statement about surface anatomy. We can place a child on our lap but there is no such thing in our skeletal anatomy as a lap. Like the shoulder it is a shape, topography, or surface anatomy only. Like the lap, when we raise our arms our shoulder disappears. Although the word shoulder is frequently used anatomically, in every such instance it is more accurate and, importantly, more perceptually meaningful if we use the word scapula instead.

Although the shoulder joint is correctly named in anatomical terminology as the glenohumeral joint, it is incorrectly understood as somehow independent of the scapula and to instead be a part of the shoulder. Superficially this may make sense but in reality it is a misnomer. The shoulder joint is just a colloquial name for a very complex and important part of the scapula. The scapula has a number of very different joint surfaces but the largest and most prominent is what we call the shoulder joint. The glenohumeral joint is a part of the scapula and nothing else, except the arm, of course.

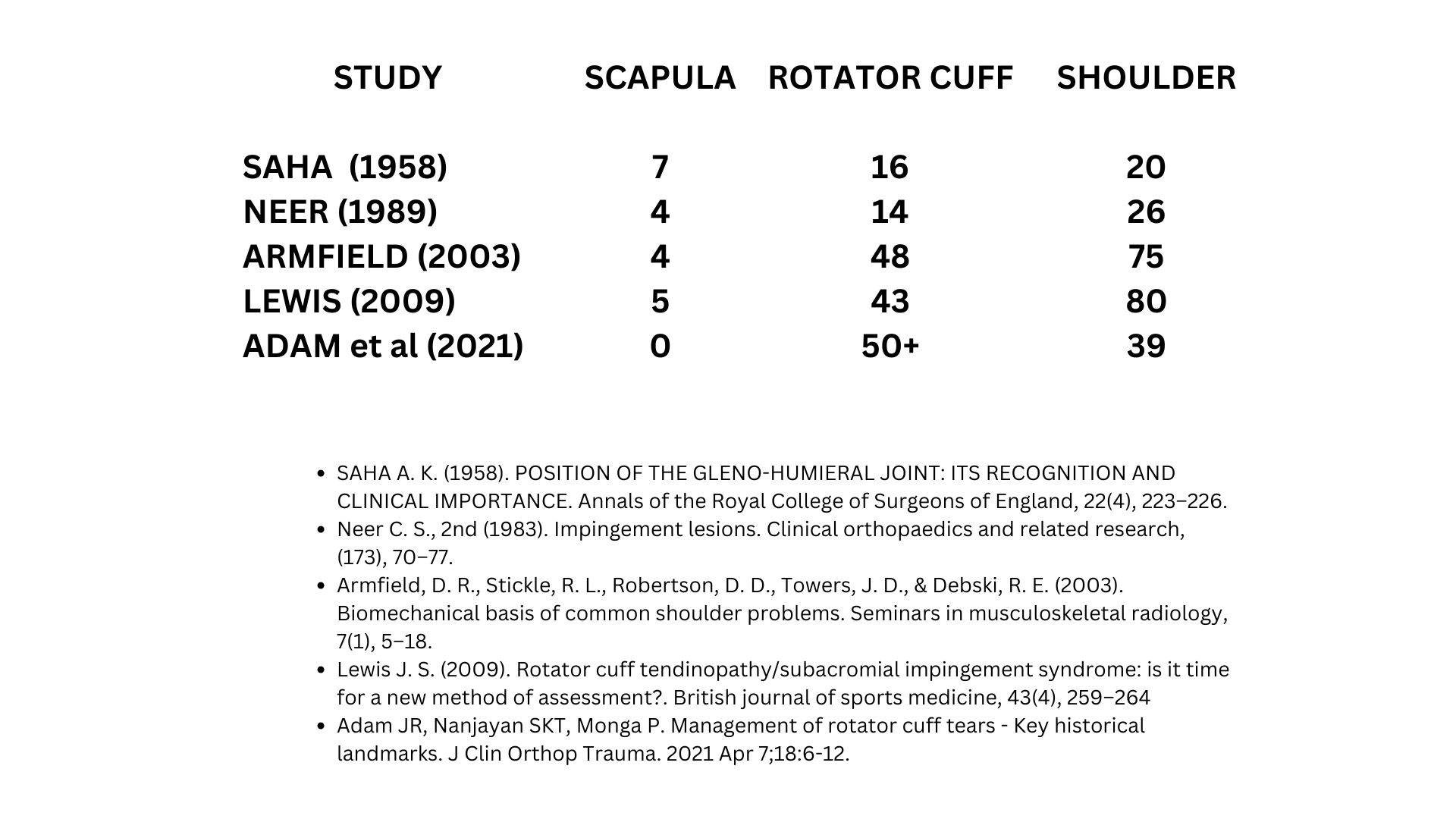

The scapula is treated dismissively and often ignored by medical authorities. It is subordinated to the shoulder joint, to the shoulder, and even to the clavicle. A review of major articles of shoulder surgery shows that the words for the shoulder joint, like the rotator cuff, and shoulder region are typically mentioned dozens of times while the word scapula occurs only infrequently if at all. This matters because anatomical specificity is of fundamental importance to shoulder surgery. If we are not talking about the scapula then we are not talking about factual anatomy.

In discussing the upper extremity, Winslow advises that “we ought not here to have any regard to the Clavicula…” (ibid).

It is widely understood that the clavicle does not exist in many species and even when “absent from birth or removed surgically much of the mobility of the arm remains” (Basamania et al. 2016). Yet, in nearly every anatomical text, in the ordering of the bones of the shoulder the clavicle is listed first. (Vesalius’s 1543 Fabrica is a notable exception.) This is because it is understood to have a “true joint”, meaning a conventional synovial joint, (Goldthwaite 1909, Codman 1943, Wikipedia Contributors 2022), while the scapula is regarded as merely floating on the back of the rib cage in what is called a syndesmosis, or floating joint. (Hermans 2010).

This celebration of the clavicle is hard to understand in light of its obvious anatomical fragility. In his authoritative chapter on the gross anatomy of the shoulder, Chris Jobe states that the clavicle is “the only skeletal articulation between the upper limb and axial skeleton” (2016). Writing about the clavicle in the surgical textbook, The Shoulder, Collins et al (2016) claim it is “the limb’s only true articulation to the axial skeleton” and “motion of the scapula on the thorax is possible only through the combined motions occurring via the sternoclavicular (SC) and acromioclavicular (AC) joints”.

This might make sense but the scapula is much larger and more powerfully attached to the body than the clavicle, which is easily broken and dislocated. The clavicle has an insecure attachment on the distal ribs, in a notch in the sternum at the front of the rib cage. There is very little good argument for its ordinal priority other than our historical belief in the shoulder and bias against the scapula.

In stark contrast to the clavicle, the scapula is located proximally—near the base of the ribs, adjacent to the spine. It has a very powerful and secure attachment to the body involving an array of 17 different muscles. Although treated dismissively, it makes clear sense to see the scapula as the center of coordination and action in the region.

Because the scapula has been subordinated in this way, it is viewed as passive kinesiologically. The muscles that attach to the scapula are described as inserting upon and acting causally upon it: for example the serratus muscles are described as originating on the distal ribs and reaching back around them, holding the scapula onto the torso. This contradicts the rules of ordinal priority in kinesiological naming and it makes much more sense to view the powerful bone of the scapula, rather than the distal ribs, as the origin of these muscles.

From this perspective the scapula is subjective and causal. The scapula is the origin or the source of these muscles, which it uses to actively reach around and hold onto the rib cage. By prioritizing and empowering the scapula, by rectifying ordinal priority, we restore awareness to the body. This has important consequences for our postural structure because the scapula not only is the center of coordination for the arm but contributes to core stabilization through its powerful relationship with the torso.

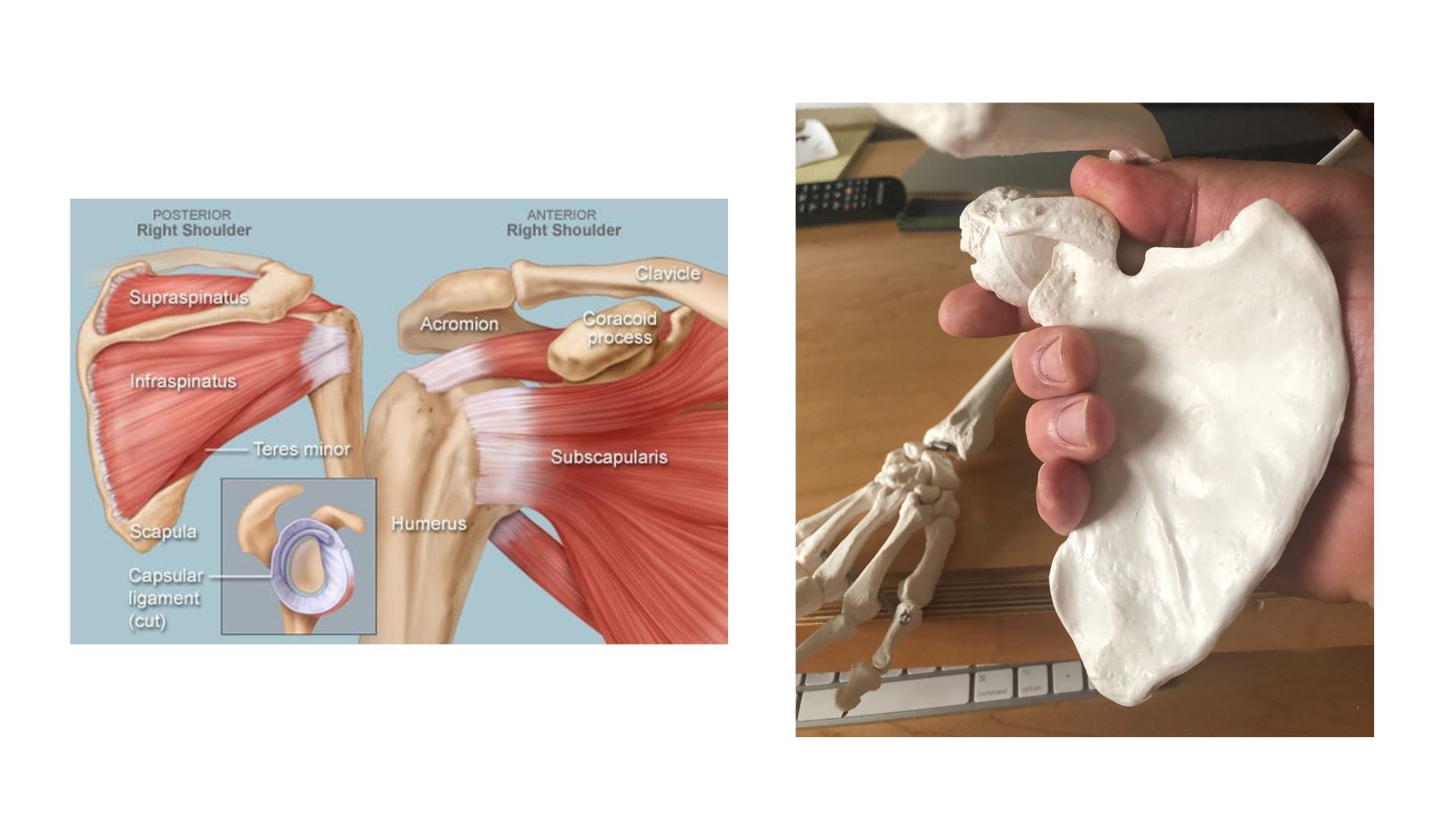

The intrinsic muscles of the scapula form the rotator cuff. These muscles attach to the grip-shaped bone of the scapula like a hand whose fingers are wrap

ped around the head of the upper arm like fingers grasping a door knob. In this way the intrinsic muscles of the scapula maintain centration and stability in the highly mobile but insecure shoulder joint.

There is an elegant symmetry between the grip formed consciously in the fingers of the hand and this deep postural foundation that exists in the scapula and the armpit. You can experience this by reaching out to shake hands or grasp an object nearby while keeping this relationship in mind. It is not difficult to sense the scapula in the highly sensitive armpit, which is designed to be intimately felt.

According to scholars like Ben Kibler scapular activation is the simple solution to most common shoulder problems. By returning activation, attention, and subjectivity to the scapula we energize the region it is at the center of. In doing so we naturally and intuitively reverse the structural imbalance responsible for the slouch. Somatically this is what it means to get a grip.

Finally it is important to recognize problems with the efficacy of shoulder surgery. It is becoming increasingly clear that these problems are due to diagnostic and anatomical confusion. A number of studies have found that statistically speaking shoulder arthroscopy is no better than no treatment or only exercise. These studies recommend much greater care in diagnosis and the preferential use of noninvasive rehabilitative approaches. Philosophically it seems that a more structural perspective and the a fundamental rectification of names is needed.

This kind of reversal of priorities is the classical justification for the rectification of names, although perhaps it is novel to apply it to our skeleton. The scapula is one of several major bones related to the deep core body map and the axial line of the body, and each of these major bones has a similar story to tell. Altogether it is the story of postural collapse syndrome, the body’s maladaptive structural response to the long-term effects of environmental mismatch and the global physical inactivity pandemic.

References

Basamania and Rockwood 2017 Fractures of the Clavicle in Rockwood and Matsen The Shoulder 5th ed. Elsevier.

Codman, E. 1934. The Shoulder. Self published. Reprint 1965. Brooklyn: G Miller and co.

Collins HA et al. 2016. Disorders of the Acromioclavicular Joint. In Rockwood and Matsen eds., The Shoulder 5th ed, Elsevier.

Goldthwait, Joel E.. An Anatomic And Mechanical Study Of The Shoulder-Joint. The American Journal Of Orthopedic Surgery S2-6(4):P 579-606, May 1909.

Hermans, J. J., Beumer, A., de Jong, T. A., & Kleinrensink, G. J. (2010). Anatomy of the distal tibiofibular syndesmosis in adults: a pictorial essay with a multimodality approach. Journal of anatomy, 217(6), 633–645.

Jobe, C. et al. (2016). Gross Anatomy of the Shoulder. In Rockwood and Matsen eds. The Shoulder 5th Edition. Elsevier.

Netter, FH. 1989. Atlas of Human Anatomy: Cuba-Geigy.

O’Brien S. et al. (2016) Developmental Anatomy of the Shoulder and Anatomy of the Glenohumeral Joint. In Rockwood and Matsen eds. The Shoulder 5th Edition. Elsevier.

Sakai T. (2007). Historical evolution of anatomical terminology from ancient to modern. Anatomical science international, 82(2), 65–81.

Wikipedia contributors n.d. Shoulder girdle. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 04:09, December 4, 2023, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Shoulder\\\_girdle&oldid=1073609553

Winslow, J. 1733. An Anatomical Exposition Of The Structure Of The Human Body. Trans. Douglas G. London: N. Prevost

Leave a Reply